Gorbachev outlines common home plan

Soviet leader explains his vision for an undivided continent in the 21st century complete with free choice and economic reform

by Hella Pick in Strasbourg

7 July 1989

President Mikhail Gorbachev yesterday outlined his vision of a ‘unified European community for the 21st century’, based on political reality and a doctrine of restraint and targeted on the creation of a ‘vast economic space from the Atlantic to the Urals’.

But in his Council of Europe address, the Soviet leader admitted that his blueprint for the common European home is far from complete. Many of the post-war certainties have gone. Change in Europe is imminent and European leaders are now engaged in a race to manage the transition to a new Europe before anarchy breaks out.

Mr Gorbachev’s perestroika, with its emphasis on political and economic reform and on free choice, has let a genie out of the bottle whose effects are almost impossible to foresee and hard to control.

His declaration yesterday, the culmination of efforts to find acceptance in the West for his drive to end the division of Europe, aims at defining the goals clearly enough to prevent the outbreak of political chaos and to narrow the East-West economic gap. He recognises that none of this can be achieved without reconciling Western interests with his own.

He has put forward some new ideas, but also many old and tired ones. There is a jumble of proposals on security, economic and environmental co-operation, and a recognition that ‘a world where military arsenals would be reduced, but where human rights would be violated, would not be a safe place’.

Mr Gorbachev was adamant that ‘overcoming the division of Europe’ was not to be interpreted as open season on socialism. The West had to accept that the states of Europe ‘belong to different systems’.

Yet Mr Gorbachev insisted ‘on the sovereign right of each people to choose their own social system at their own discretion’ and said he could envisage ‘a change in the social and political order in some countries’.

During each of his visits to Western Europe this year, the Soviet leader has been adamant that there was no design to decouple Western Europe from Nato or to detach West Germany from its western alliance.

Mr Gorbachev repeated this yesterday, declaring that ‘the Soviet Union and the United States are a natural part of the European international and political structure. Their involvement is not only justified, but also historically conditioned. No other approach is acceptable’.

The Soviet Union has put out feelers for a superpower summit later this year where European issues would have priority. But yesterday Mr Gorbachev spoke only of his proposal for a pan-European summit. It was high time, he asserted, for the successor generation to the leaders who signed the 1975 Helsinki Declaration to meet and review the options for a European Community in the 21st century.

This is an edited extract. Read the article in full.

Editorial: rather, the street where we live

7 July 1989

It is not a European home that we need, but a European street of relaxed neighbours. Put us all together - different clout, different systems - under one roof, and there would be domestic strife. That is the history of the old, bad, warring Europe. Set us side by side along an avenue and who knows what, in the end, may appear?

Gorbachev tells allies to pursue own paths

8 July 1989

President Gorbachev hailed a ‘new spirit’ in the Warsaw Pact yesterday, telling his East European allies that each should be free to pursue its own path and respect that of others. ‘There is a new spirit within the Warsaw Treaty, with moves towards independent solutions of national problems,’ he said on the first day of the seven-nation alliance’s annual summit.

Mr Gorbachev, whose perestroika reform programme has brought to the surface long-standing tensions inside the pact, made clear he had no intention of using the Soviet Union’s dominance of the alliance in favour of either side of the reform argument. ‘We recognise the specifics of our parties and peoples on their path towards socialist democracy and further development,’ he said.

Mr Gorbachev was addressing the leaders of the pact’s member states at a dinner in the banqueting hall of Bucharest’s presidential palace. The alliance has concluded discussion on documents due to be signed today, which will call for more dialogue with the West on disarmament and lay out a vision of a world free of nuclear and chemical weapons.

The pact appears more openly divided than at any time in its 34-year history over the pace of reforms to overcome mounting economic crisis and political stagnation. Moves by Poland and Hungary to end their Communist parties’ four-decade monopoly of power have angered the ageing leaderships in Romania, East Germany, and Czechoslovakia.

Mr Gorbachev demonstrated his even-handed approach by holding talks with Hungary’s newly-elected reformist leader, Mr Rezso Nyers, while also displaying deference at the official banquet to Czechoslovakia’s ailing hardline President, Gustav Husak. Apparently referring to the documents to be signed today, the Soviet leader said the pact had taken new steps to promote European security and dialogue between East and West.

In recent times, there had been a new atmosphere, with the pact and Nato each willing to listen and talk to the other, he said. ‘But there is still a war psychosis which we must overcome,’ he added. ‘We think it is necessary to stress the need for a shift from military to political moves.’

Mr Gorbachev was addressing the dinner in his capacity as host of next year’s summit, which will be held in Moscow.

Heady ideas of East and West unleash forces of change across Europe

by Hella Pick, diplomatic editor

14 July 1989

If imagery alone counted in the superpower skirmishing over Europe’s future, then Mr Mikhail Gorbachev would win hands down with his ‘Common European Home’. The West has readily taken to discussing its architecture, its furnishing, even the rules that would govern the administration of the condominium.

The Bush doctrine is about a ‘Commonwealth of European Nations’, a concept that is not easily translated into building bricks; all the less so when the Soviet Union suspects the President of seeking to roll back communism in Europe.

But the two presidents have not been wooing Europe so assiduously merely to see which can coin the better phrase. Each is concerned to influence a continent in flux, and to maintain a modicum of stability at a time of far-reaching political change in a Western Europe dominated by the evolving EC, and in an Eastern Europe where Marxism has to come to terms with political pluralism and the market economy.

Mr Bush and Mr Gorbachev have succeeded rather better at exposing deep-seated problems than devising the solutions. They recognise that the East-West prosperity gap may turn out to be far more destabilising than the now diminishing military confrontation in Europe.

The US President has learned first-hand, especially in Poland, that the trend towards democracy in Eastern Europe is not just undermining Soviet influence, but also creating political uncertainty and provoking impossibly high expectations of Western economic support.

Mr Gorbachev has seen, especially in West Germany, that many Europeans have exaggerated confidence in his ability to guarantee peace in Europe.

Even though the two leaders profess themselves eager to co-operate in Europe, they remain deeply suspicious of each other’s intentions and it is unclear how much convergence there is in their European policies.

Mr Gorbachev has developed a complex, not always coherent, picture of his aims in Europe. The Bonn Declaration, signed between the Federal Republic and the Soviet Union, is a formal repudiation of the Brezhnev doctrine of limited sovereignty. It also incorporates the Soviet leader’s conviction that the US and Canada must be part and parcel of the European common home.

It promises ‘peaceful competition’ and an enduring commitment to human rights. It points to disarmament and arms control as the key to strengthening the fabric of peace in Europe; but in deference to the Nato doctrine of nuclear deterrence omits any reference to President Gorbachev‘s belief in a Europe free of nuclear weapons.

The declaration refers to the Nato and Warsaw Pact alliances, and assumes that the two political camps in Europe would be maintained.

Yet in Strasbourg last week, Mr Gorbachev warned that there were limits to change in Eastern Europe. ‘Overcoming the division of Europe’ was not to be confused with ‘overcoming socialism in Europe. There will be no European unity along these lines ... this is a course for confrontation.’

The Soviet leader is deeply suspicious of Mr Bush’s interest in Eastern Europe and uncertain whether the logic of the US policy might not be to drive as many Eastern European countries as possible out of the Soviet orbit.

President Bush has not tried to match Mr Gorbachev in expressing his ideas about overcoming the division of Europe. It is not certain that he is clear in his own mind how far the encouragement of democracy in Eastern Europe can safely be taken. It is easy enough to interpret Mr Bush’s actions in Poland and Hungary as a conscious decision to exploit the Gorbachev-inspired political reforms for extending the West’s zone of influence. That is certainly how the Bush call for the withdrawal of all Soviet troops from Poland was construed in Moscow.

Yet, the US President has also been very careful to insist that it is not his intention to undermine Soviet security interests in Europe. This suggests that Mr Bush is ready to accept that the countries of Eastern Europe should maintain their membership of the Warsaw Pact, and that German self-determination is not on the agenda, at least for the foreseeable future.

The question that neither leader can answer satisfactorily is what forces their policies have let loose in Europe. In the West, Germany has reclaimed a decisive role in Europe. In the East, Poland and Hungary are finding their own voice again. Others may follow. For the time being, they are willing to recognise the geopolitical constraints imposed by Moscow, like membership of the Warsaw Pact. But independence and democracy are heady ideas, and neither Bush doctrine nor the Common European Home may be able to contain them.

This is an edited extract. Read the article in full.

On 9 November 1989, the East German government opened the country’s borders with West Germany (including West Berlin), and openings were made in the Berlin Wall through which East Germans could travel freely to the West. A month later, the Guardian published a series of articles about the new Europe, with Martin Woollacott setting the scene.

Europe Tomorrow: The climb to the sunlit uplands - Planning for a new Europe

by Martin Woollacott

4 December 1989

This week, as President Gorbachev travels Europe and meets President Bush in the wake of the most momentous events since the end of the Second World War, the European Community leaders meet in Strasbourg to shape the single European market for the nineties. But they must also begin planning for a new Europe in the twenty-first century, with a Community that might include more than a score of nations and many associated countries as far east as Azerbaijan.

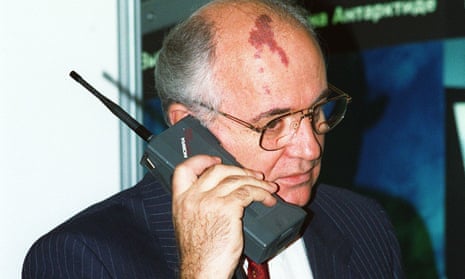

A vital element in the amalgam that is the new Europe has been of course Mikhail Gorbachev. We now see more clearly how desperate a situation he found himself in when he took over in 1985. The economy was in terminal condition. If the USSR was to remain a world power reforms were necessary - but as reforms were undertaken, they revealed the need for yet more reforms, moving from economic re-organisation to a freer press to the attempt to establish a ‘socialist pluralism.’ Gorbachev represented more than expediency, however. He represented, and represents, that large new Soviet middle class - educated, professional, morally concerned, partly westernised - which is itself one of the important European developments.

It is too simple to see everything as springing from that day in March 1985 when Mikhail Gorbachev became Secretary-General of the Soviet Communist Party. The Europe we begin to see was in process of preparation on many fronts. The stubborn preservation of alternative politics in Eastern Europe and their flowering, above all, in the Solidarity movement; the modernisation of Latin Europe and the re-dedication of France, in particular, to the Community; the refusal of both Germanies, even at the height of the Second Cold War, to wholly buckle under to their respective Alliance leaders; and now the courage of East Germans, followed by Czechs, in demanding change - all were as necessary to transformation as the movement for reform in the Soviet Union and the winding down of the Warsaw Pact and Nato war machines. Thus it is that we have that conjunction between reform in the East and renewal in the West that represents such an opportunity for the old Continent.

This is and edited extract. Read the article in full.